Fishes of Canada's National Capital Region

Brian W. Coad

Canadian Museum of Nature,

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Contents

Updates (significant new information not in the main text)

Species Accounts (species descriptions, biology, figures, maps)

Checklist (official scientific, English and French names)

Keys (for identification)

© Brian W. Coad (www.briancoad.com)

This work is a guide to the fishes found in the National Capital Region (NCR) of Canada, a region encompassed by a circle of 50 km radius centred on the Peace Tower of the Parliament Buildings in Ottawa, extending into Ontario and Québec. An earlier work by Coad and McAllister (1975) is dated and required a revision. The book treated 75 species while this work covers 84 species and, as the updates show, species new to the NCR are still being recorded.

Most illustrations are of fishes and localities from within the NCR although some are from other sources, as noted when a cursor is placed over them. Maps can be clicked on to show a larger version with caption details.

Additions to the main text of this website terminated in 2010. However, some notes and updates will be added here if they are deemed significant. Descriptions and keys to species new to the NCR and not in this text can be found in Scott and Crossman (1973) and Coad et al. (1995).

• A tilapia, believed to be the Blue Tilapia (Oreochromis aureus (Steindachner, 1864)), has been found in a stormwater retention pond in Ottawa (Nicholas Mandrak, pers. comm., 23 June 2010). It is probably a released aquarium fish and does not probably represent an established population.

• The Central Stoneroller/Roule-caillou (Campostoma anomalum (Rafinesque, 1820), Cyprinidae) has been collected in the Jock River at Bleeks Road (Brian Bezaire, pers. comm., 9 June 2010), a new record for the NCR. Stonerollers have been seen in Ottawa bait shops for many years.

• The Bridle Shiner/Méné d'herbe (Notropis bifrenatus (Cope, 1867), Cyprinidae) has been captured in the Rideau River at localities near James Island (Jason M. Barnucz and Brian Bezaire, pers. comm., 9 June 2010), a new record for the NCR.

• Photographs of a fish caught in April 2010 at Victoria Island in downtown Ottawa (courtesy of Tim Haxton, 22 April 2010) appear to be a White Bass/Bar Blanc (Morone chrysops (Rafinesque, 1820), Moronidae). This new species record for the NCR needs confirmation with voucher specimens.

Central Stoneroller, Bridle Shiner and White Bass

• Lampreys, as yet unidentified, have been caught in the Bearbrook watershed east of Ottawa (North Indian Creek and an unnamed tributary of the Bearbrook) (Josh Mansell, South Nation Conservation, 31 March 2011).

Scientific Name: Acipenseridae Amiidae Anguillidae Atherinopsidae Catostomidae Centrarchidae Clupeidae Cottidae Cyprinidae Esocidae Fundulidae Gadidae Gasterosteidae Hiodontidae Ictaluridae Lepisosteidae Osmeridae Percidae Percopsidae Petromyzontidae Salmonidae Sciaenidae Umbridae

English Name: Bowfins Carps and Minnows Cods Drums and Croakers Freshwater Eels Gars Herrings Lampreys Mooneyes Mudminnows New World Silversides North American Catfishes Perches Pikes Sculpins Smelts Sticklebacks Sturgeons Suckers Sunfishes Topminnows Trout-perches Trouts and Salmons

French Name: Achigans et Crapets Anguilles d'eau douce Barbottes et Barbues Brochets Carpes et Ménés Catostomes Chabots Éperlans Épinoches Esturgeons Fondules Harengs Lamproies Laquaiches Lépisostés Morues Omiscos Perches et Dards Poissons d'argent Poissons-castors Tambours Truites et Saumons Umbres

The Species Accounts are listed above alphabetically by families under scientific name, English common name and French common name. In the text below, the families and their included species are arranged taxonomically, as is traditional, and the links above help locate the families.

Species Accounts are preceded by a family account where general characters and biology shared by all members of the family are explained to avoid repetition under each species. Families with only a single species in the National Capital Region (NCR) may have only a few comments here as characters and biology are subsumed in the Species Account. Further information on the fishes can be found in Encyclopedia of Canadian Fishes (Coad et al., 1995). Some of the NCR fishes are also found in marine waters where their biology can be quite different. The higher relationships of the fishes and further information on their relatives in other parts of Canada are also dealt with in that work.

Layout of Species Accounts

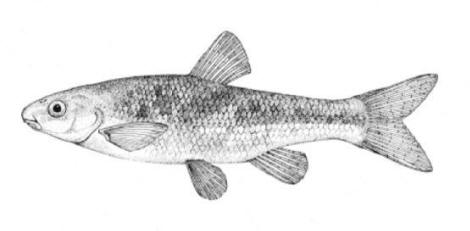

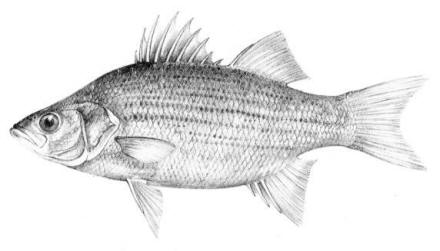

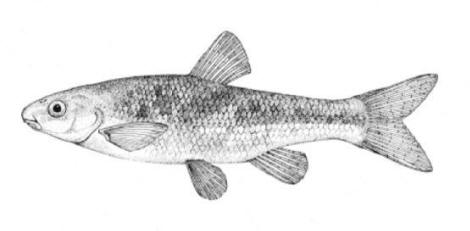

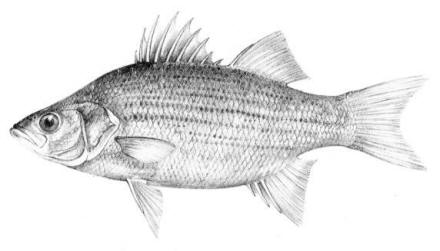

Species Accounts are comprised of a line drawing, colour drawings, colour photographs of fish and fish habitats where available, a spot distribution map and a text with taxonomy, key identification characters, a description of the species including colour and size, general distribution, origin, habitat, biology and importance. The species are arranged by scientific name within each family so related fishes are next to each other.

Maps can be clicked on to show a larger version. Colour drawings and photographs have data available by running a cursor over them.

Unattributed statements in all parts of the Species Accounts are based on a survey of the general literature for the species and may not always apply in the NCR. For example, Lake Sturgeon are described as occurring in lakes (as the common name indicates) but in the NCR they are found only in the Ottawa River. Referenced items or items which specifically mention areas within or near the NCR carry local information.

The line drawing shows characters which may not be evident on a photograph, colour photographs show natural colours and variations as well as size and shape, and habitat photographs give a pictorial summary of habitats.

The spot map shows capture localities based on preserved specimens in the Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa and other museums (susceptible to re-examination and correction), and on literature records, records from websites, and anecdotal accounts judged to be accurate reports (but not susceptible to re-examination other than further field work). Coad (1985a) gives a report on an error of distribution, for example, and many others have been analysed for this study. Certain records of species have been rejected as there are no voucher specimens available for confirmation and they have not been reported from the NCR in other literature records. Efforts to collect unusual literature records in the field were made without success: they are most probably misidentifications.

All localities are stored in a database. The commoner species with a wide tolerance of environmental variables and easily capturable are much more widely distributed than these spots might suggest while the rarer species, with few spots, are probably a more accurate reflection of distribution. Phelps et al. (2000), for example, captured over 6900 fishes in less than two months on the Rideau River but only one of these was a Freshwater Drum. Records also reflect ease of capture, itself a reflection of gear used, time of use, effort and simple luck. Sport fishes may have fewer localities since they may have restrictions on licensed collecting or localities may be kept secret to protect stocks. Some rivers or lakes have been intensively surveyed while others have been sampled only sporadically and/or at widely separated localities.

A map showing all localities sampled can be accessed here.

Taxonomy gives some other common names, reviews changes in scientific names, reports hybrids and covers other systematic and taxonomic problems.

Key identification characters separate a species from others within its family and from other fishes in the NCR. These key characters are only applicable within the NCR. However some species have obvious and unique characters which separate them from all other fishes. Some fishes are more subtly distinguished and characters in combination may have to be used or body proportions. Body proportions are often not as clearly defining as unique structures or countable characters, varying with growth, maturity or even fullness of the gut. Countable characters may overlap in ranges. The separate section of Keys should also be consulted.

The species description is based on specimens from within the National Capital Region and on others from elsewhere in Canada and North America. The range for meristic characters is given for the species as a whole. Counts based purely on local fish or on a few specimens may give a misleading impression of the potential range should more specimens be examined.

Colour is based on specimens when alive but may also have details only visible on preserved fishes.

Size gives length, usually total length, but sometimes standard or fork length.Where the type of length is not indicated this is because it was not given in the source. Weights are not always known for the smaller species. Record fishes caught by angling may also be cited. Since fish grow continuously, although much more slowly with age, there is no definitive maximum size and larger specimens may always be caught.

Origin gives the refugium from which the species entered the NCR as the there were no fishes here until the glaciers retreated after the last ice age. A history of the area and detailed routes and timing of entry are given in McAllister and Coad (1975), Rubec (1975a), Bailey and Smith (1981), Legendre and Legendre (1984) and Mandrak and Crossman (1992).

Habitat gives details of the environment in which the species is found.

Distribution places the species in context for North America and the world and some features of distribution in the NCR may be discussed.

Biology sections (Age and Growth, Food and Reproduction) are based firstly on that known for the species throughout its range with notes from local fishes where available. Few local fish populations have been studied intensively. Time of reproduction, for example, will vary with local conditions such as temperature but is seasonally the same for the species across Canada. Details of diet will also vary depending on availability of food species in the habitat type or region of the country but will be generally similar. Growth depends on food supply, competition, and various environmental factors.

Importance gives details of the significance of the species commercially, recreationally and biologically. Some species have "none" under this heading, indicating that they are not significant commercially or recreationally and that their biology is poorly known, although any species has importance in its ecosystem. Dymond (1939) provides a review and accessible summary of fisheries in the general vicinity of the NCR in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century while noting fisheries data is recorded from different areas at different dates making comparisons difficult. In 1898 over 700,000 lbs (317,518 kg) of fish were taken from the Ottawa region (which includes some waters outside the NCR as defined here), of which 70,300 lbs (31,888 kg) were bass (presumably Smallmouth Bass) and 37,750 lbs (17,123 kg) Muskellunge. This level of fishing, coupled with pollution (particularly sawdust), steadily depleted stocks.

Petromyzontidae - Lampreys - Lamproies

Lampreys are found in cooler waters of the northern and southern hemispheres. There are 41 species with 11 recorded from Canadian freshwaters and along all three coasts. There are 4 species in the NCR.

Lampreys are jawless fishes, lacking bone in the skeleton and having 7 pairs of pore-like gill openings. The eel-like body has no pectoral or pelvic fins. There are 1 or 2 dorsal fins and a caudal fin. An anal fin-like fold develops in spawning females. Eyes are large. The mouth is a suctorial disc armed with rows of horny teeth. There are also teeth on the tongue. The median nostril, or nasohypophyseal opening, is not connected to the mouth. There is a light-sensitive pineal organ or "third eye" behind the nostril. The skin is covered in mucus which is poisonous to fishes and humans. Lampreys are edible if the mucus is cleaned off. Lampreys have a body form similar to the more familiar but unrelated eels (Anguillidae). Occasionally there are references in articles to lamprey-eels, but there is no such fish; there are lampreys and there are eels, quite distinctive organisms.

Their origins lie at least 300 million years in the past. Their tooth arrangement is used in classification and identification along with the number of myomeres (muscle blocks along the body). Both tooth counts and the number of cusps are used in particular those on the supraoral lamina (bar above the "mouth", the oesophageal opening), the infraoral lamina (bar below the "mouth") and the row of teeth on both sides of the "mouth". There are various series of smaller teeth and of course teeth on the tongue. Larval lampreys lack teeth and are particularly difficult to identify and their determination often requires specialist knowledge. Characters for the larvae include counts of myomeres and pigmentation patterns.

Lampreys have an unusual life cycle. Adults die after spawning and the eggs develop into a larva, known as an ammocoete, which lacks teeth, has an oral hood, eyes covered by skin, a light-sensitive area near the tail, and is a filter-feeder while buried in mud and silt. Fleshy tentacles in the oral hood are used to extract minute organisms from the water, such as algae (desmids and diatoms) and protozoans. After several years (up to 19 but usually 7 or less), the ammocoete transforms into an adult with enlarged eyes, teeth, a different colour and pronounced dorsal fins. The body shrinks during this metamorphosis and adults are only larger than ammocoetes if they feed. The adult may be a parasite on other fishes and marine mammals, or non-feeding. Individuals of a species may or may not be parasitic and different species may be parasitic or non-parasitic. The non-parasitic species are believed to have evolved from a parasitic species so there tends to be closely related parasitic/non-parasitic species pairs.

Parasitic adults feed mostly on other fishes, attaching to their bodies by suction and using their toothed tongue to rasp through the skin and scales to take blood and tissue fragments. Prey is detected by sight but some lampreys attach to hosts during the night. Perhaps this reduces their own predation risks and enables them to approach their quiescent hosts more easily. Lampreys tend to select larger fish as these survive longer and ensure a good food supply. The flow of blood is aided by an anti-coagulant in lamprey saliva called lamphedrin which also serves to break down muscle tissue. Large, anadromous lampreys are usually attached ventrally near the pectoral fins while small, freshwater species, such as the Chestnut Lamprey and the Silver Lamprey, are usually attached dorsally. Dorsal attachment reduces abrasion of the lamprey in shallow water. Ventral attachment results in greater food intake for the lamprey. Lamprey attacks leave a characteristic round scar and can be a major problem for commercial fisheries by damaging food species and leaving them too unsightly to market. The attack may weaken or even kill the host. Weakened fishes are more prone to diseases and the wound provides an easy path of entry for them. Even fishes with heavy scales like Gar Family members are attacked. A single 16 kg Lake Sturgeon has been recorded with 61 Silver Lampreys parasitising it, although it was estimated that this would not kill the host by draining its blood.

Lampreys may move into or up streams to spawn. The scientific name of the family means "stone sucker" and the adult mouth is used to hold or suck onto stones as well as on prey. This suction enables the lamprey to maintain position in fast-flowing streams when spawning and even to climb over rapids and small waterfalls. Usually spawning occurs in shallow water with a moderate current, a bottom of gravel and nearby sand and silt for the ammocoetes to live in. Either or both sexes build a nest by moving gravel around with their sucking mouths and by thrashing their bodies. A shallow depression is formed, about 0.5-1 metre long. Spawning often occurs in groups and several males may attach to a female with the sucking disc. The process takes several days as only a few white to yellow eggs are laid at a time. The eggs are adhesive.

Adult lampreys are usually caught when attached to a host or when spawning. Electro-shocking will force ammocoetes out of their u-shaped burrows to the surface and immobilise adults. They sometimes attach to boats and occasionally to swimmers when their skin is cool but are easily removed, perhaps because nobody has left a lamprey on their skin long enough to see if the tongue starts rasping flesh!

Lampreys have been used for food by various native peoples in Canada and are popular in Japan. They have been considered a delicacy and can be smoked, set in aspic or cooked in a variety of ways. Henry I of England is said to have died of a "surfeit of lampreys".

Chestnut Lamprey / Lamproie brune

Ichthyomyzon castaneus Girard, 1858

Taxonomy

Other common names include Western, Northern, Silver, and Brown Lamprey, Hitchhiker, Seven-eyed Cat and Bloodsucker. Ichthyomyzon is from the Greek ichthys for "fish" and myzon for "sucking" and castaneus is Latin for "chestnut-coloured".

Key Characters

This lamprey is distinguished by having a single, notched dorsal fin, by having 1 or more lateral disc teeth with 2 cusps (1-10 bicuspid circumorals, usually 6).

Description

There are 47-57 trunk myomeres, usually 51-54. Teeth are sharp, strong and curved. The band of teeth below the mouth is a broad, curved bar with 6-11 tooth cusps. There are 4 pairs of inner lateral teeth, usually bicuspid and sometimes tricuspid.

Colour

Adults are dark grey to olive, or yellow-brown, sometimes mottled, occasionally a chestnut colour which gives them their name. The lateral line organs are black in adults, though only weakly in young adults. They become blue-black when spawning. Ammocoetes are overall lighter in colour. Ammocoetes are paler and have no pigment, or are only weakly pigmented, on the lateral line organs.

Size

Attains 38.0 cm.

Found in central North America from southeastern Saskatchewan, west-central Manitoba and eastern Lake Huron tributaries of Ontario south to the Gulf of Mexico centred on the Mississippi-Missouri basin.

Origin

This species entered the NCR from a Mississippian refugium.

Habitat

Found mostly in medium-sized streams although adults may be found in large rivers and dams. Ammocoetes prefer vegetated areas with current unlike other species.

Age and Growth

Ammocoete life span is unknown, but is presumed to be 5-7 years with a maximum age for the species of about 8 years.

Food

Transformed adults do not feed over their first, and one subsequent, winter and feed most heavily from April to October. They spawn and die the following summer. This species has been caught attached to a Lake Sturgeon or a Northern Pike in Brewery Creek in the NCR (the data were uncertain), most probably the latter given the locality (Renaud and de Ville, 2000). The eggs of this lamprey are eaten by darters, minnows and crayfishes.

Reproduction

Peak spawning is in early to mid-June at 15.6-22.2°C in Michigan and takes place at night in small to large groups (up to 50). A female attaches to a stone and begins rapid quivering motions. A male attaches to the head of the female and wraps its tail around her body. Up to 5 lampreys can attach, each to the head of the one before it. Up to 50 lampreys can be found in a single nest as nests tend to merge during excavation. The nest sites are in small streams. A single nest can be 2.8 m long and 1 m wide. The spawning continues through the night but by the afternoon of the following day, lampreys have left the nest. A large female had 42,000 eggs. Eggs are elliptical, 0.64 mm by 0.56 mm.

Importance

This lamprey was accorded a status of "vulnerable", now "Special Concern", in 1991 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. It is not as economically significant as the Silver Lamprey because of its habitat, size, abundance and distribution in Canada. Elsewhere it is known to attack Brook Trout and can stay attached for over 18 days, killing the host. Trout destruction has been reported as reaching 23.5 kg/ha or about one-third of the trout available to anglers. They are a favoured food of Burbot and trouts as well as other fishes.

Northern Brook Lamprey / Lamproie du nord

Ichthyomyzon fossor Reighard and Cummins, 1916

Taxonomy

Other common names include Michigan Brook Lamprey and Blood Sucker.

Key Characters

This species is distinguished from other Canadian lampreys by having a single dorsal fin, teeth along the side of the mouth with 1 cusp, 2 knob-like and blunt cusps on the bar above the mouth, 6-11 knob-like and blunt cusps on the bar below the mouth, and lateral lines organs unpigmented.

Description

Trunk myomeres number 47-58, usually 51-54. The sucking disc is narrower than the body.

Colour

Adults are dark slate grey to brown above, pale grey, silvery or white on the belly. The area under the gill pores may be orange. Fins are grey to yellow or brown. The eye is bluish. Lateral line organs lack black colouration. In ammocoetes, the caudal fin and head are weakly pigmented.

Size

Attains 28.2 cm and 9.9 g.

Found in the Hudson Bay drainage of Manitoba, the Great Lakes basin of Ontario and the upper St. Lawrence River basin in Québec south to Kentucky and Missouri. The presence of this species in the NCR is uncertain (Coad, 1986b). Adults are not easily caught with nets because of their elongate shape and, being non-parasitic, cannot be found attached to fish. Ammocoetes can be caught in mud or sand by electroshocking but are very difficult to identify and distinguish from the Silver Lamprey. Spawning adults would be readily identifiable but attempts to catch them have failed as spawning takes place in early spring when water levels are high, conditions are difficult of access in flooded areas of uncertain depth. Lanteigne (1981; 1992) mapped the Northern Brook Lamprey at Ottawa but Rohde and Lanteigne in Lee et al., (1980) did not.

Origin

This species entered the NCR from a Mississippian refugium (Mandrak and Crossman, 1992).

Habitat

This is a non-parasitic species found in warmer streams and smaller rivers than the American Brook Lamprey or along the margins of larger rivers. It is reported as common in turbid streams. Ammocoetes prefer a soft bottom over firm sand but not the extremely soft mud of backwaters. They are most numerous at 15-61 cm depths. They move only if their habitat is disturbed or food becomes short. This movement takes place mostly at night when predators are less active. Low fertility and relatively low mobility as a non-parasitic species make it vulnerable to natural and man-made habitat changes.

Age and Growth

Ammocoetes live 5-7 years and may "rest" for a year without feeding before transformation to the adult in August to September. Maximum life span is about 8 years.

Food

Ammocoetes filter feed on desmids, diatoms and protozoans. Food may also be taken from the sediment. The gut degenerates at the beginning of transformation from ammocoete to adult and for a period of 8-9 months no food is taken. Various predatory fish will take ammocoetes and spawning adults on nests are most vulnerable.

Reproduction

Spawning occurs from late May to mid-June at 12.8-23.3°C in Michigan without a migration. The nest is constructed among large stones or gravel to create a cavity. Unusual vertical body movements, and transport of gravel using the sucking disc, excavate a 10 cm long nest. Up to about 2,000 eggs of 1.0-1.2 mm diameter are produced and adhere to silt-free sand. Incubation takes 9 days at 18°C. The post-spawning period lasts only a few days and then all the spawning adults die.

Importance

Ammocoetes have been sold as bait in Quebec but this now prohibited. This species was accorded the status of "Special Concern" in 1991 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (Lanteigne, 1992; COSEWIC, 2002).

Silver Lamprey / Lamproie argentée

Ichthyomyzon unicuspis Hubbs and Trautman, 1937

Taxonomy

Other common names include Northern Lamprey and Brook Lamprey. The Northern Brook Lamprey is its non-parasitic relative.

Key Characters

This species is distinguished by having a single dorsal fin, all teeth along the sides of the mouth with 1 cusp, (0-2 bicuspid circumorals, usually none), a sharp bicuspid tooth on the bar above the mouth, and 5-11 sharp, triangular cusps on the bar below the mouth.

Description

Teeth are sharp and yellow. Trunk myomeres number 47-57, usually 49-52. The sucking disc is wider than the body.

Colour

Adults are brown, blue-grey or bluish with silvery overtones and with a blue-grey or silver belly. Lateral line organs are black in specimens greater than 150 mm length. Adults become darker as the spawning season approaches and are blue-back near the end of spawning. Ammocoetes are pale although the caudal fin and head are strongly pigmented.

Size

Attains 38.1 cm.

Found from Manitoba, through southern Ontario around the Great Lakes to western Québec and as far south rarely to Mississippi. In the NCR this species is known only from the Ottawa River and mouths of tributary rivers. Small (1883) reports Icthyomyzon Argenteus (sic) (= I. unicuspis) from the "Rideau, Gatineau, the Lievres, and streams running into these rivers" but this has not been borne out by field work since then

Origin

Silver Lampreys entered the NCR from a Mississippian refugium.

Habitat

This is a parasitic species found in the larger rivers and lakes. Ammocoetes live in burrows in soft bottoms.

Age and Growth

Ammocoetes live 4-7 years before beginning transformation in late fall. Adults live 12-20 months and may migrate to a lake to feed. Females grow faster than males and attain a larger size.

Food

Ammocoetes filter-feed phytoplankton and other small organisms from the water. Adults are parasites on Lake Sturgeons, Brown Bullheads, American Eels, White Suckers, Silver Redhorses and Shorthead Redhorses (McAllister and Coad, 1975), on Northern Pike (attached to the inside of the branchial cavity of one pike, C. B. Renaud, pers. comm., 2002) and on Muskellunge (Renaud, 2003) in the NCR. Marks per host based on 15 Muskellunge from the Ottawa River from Ottawa to Hawkesbury varied between 1 and 31, with a mean of 10.6. 84.6% of the Muskellunge had marks on the dorsal surface, 46.2% laterally and 15.4% ventrally. The position of attachment was thought to be a consequence of the predatory behaviour of the Muskellunge, lying in concealment with the belly less exposed than in pelagic species, and perhaps to avoid detachment or injury by abrasion on the substrate. The wounds on the Muskellunge suggest blood feeding as they were shallow, rather than flesh feeding. The lampreys fed actively from at least 21 June to 30 October when captures with fresh marks were made.

Reproduction

Both sexes construct the nest in gravel in running water. Comtois et al. (2006) report fish in reproductive stage V (spawning) in the lower Gatineau River from 13 May to 23 June at 12.5-19ºC. Spawning occurs in May-June, peaking in early June, at 12.8-22.8°C in Michigan. Up to 65,000 eggs of 1.0 mm diameter may be produced. The eggs hatch after 7-10 days, depending on water temperature.

Importance

The ammocoetes are used as bait for sport fish.

American Brook Lamprey / Lamproie de l'est

Lampetra appendix (DeKay, 1842)

Taxonomy

Also called Brook Lamprey or Small Black Brook Lamprey. Scientific names used in other works that may be this species are Lampetra lamottenii Le Sueur, 1827 and Lampetra wilderi Jordan and Evermann, 1896. The former name has priority but there is some confusion over Le Sueur's application of this name and L. appendix is the next available name. Lampetra is from the Mediaeval Latin for "lamprey" and appendix is Latin for "appendage", probably referring to the prominent urogenital papilla of adult males.

Key Characters

This species is distinguished by having 2 dorsal fins, the bar above the mouth with 2-3 pointed cusps, and teeth along each side of the mouth bicuspid and pointed.

Description

Trunk myomeres number 63-74. The bar below the mouth has 6-10 cusps. Teeth are generally blunt and not as sharp as in the parasitic Silver Lamprey. Shrinkage of adults over winter from non-feeding almost closes the gap between the dorsal fins.

Colour

Adults are blue-grey when spawning with orange tinges on the head, back, tail and fins. Otherwise brown or lead-grey is the overall colour, the belly is white to light grey or silvery and clearly set off from the flanks. Fins are yellowish with the caudal fin darkest near the base, becoming lighter towards the margin. Ammocoetes are pale brown and have a whitish band above the branchial openings.

Size

Attains 31.7 cm (perhaps 35 cm) but these were "giants" which may have fed parasitically. Usually up to about 21.7 cm.

This species is found from the Great Lakes basin of Ontario and the Upper St. Lawrence River basin in Québec southwards to Virginia, Tennessee and Missouri.

Origin

This lamprey entered the NCR from possibly a Mississippian refugium or Atlantic coastal refugium (Mandrak and Crossman, 1992).

Habitat

This is a non-parasitic species found in cooler (9-12°C) small streams and rivers than the Northern Brook Lamprey. It is sensitive to environmental change and prefers water that is clean and free of silt. Around Kettle Island and Upper and Lower Duck Islands in the large Ottawa River it is found unusually in sandy areas at 13-25°C (Lanteigne et al., 1981). It does not migrate.

Age and Growth

Ammocoetes live 4-6 years (perhaps 7.5 years) and transformation begins in the fall and continues over winter. The adult shrinks without food from parasitism.

Food

Adults do not usually feed and ammocoetes filter fine particles from the water.

Reproduction

Spawning occurs in mid-May to early June in Québec at 17°C and in Ontario in April-May. Comtois et al. (2006) report fish in reproductive stage V (spawning) in the lower Gatineau River from 3 May to 20 May at 9-14ºC. In Minnesota it occurs during late April and early May at 8.7-15.5°C. In Delaware spawning occurs in March-April at 6.8-12.0°C and in Michigan at 6.7-20.6°C in early May. Nests up to 30 cm long are built to a depth of 4 cm below the stream bottom. Current velocity in a Minnesota study was 14 cm s-1. The male begins construction and the oval to circular nests are in gravel and cobble between larger rocks or just upstream of riffles. Up to 25 lampreys may spawn in one nest with 5 times as many males present as females. The male uses his sucker to attach to the female's head, arching his body to bring his cloacal region close to the female's. Nests tend to be larger in deeper water, slower current and where larger spawning groups are found. Up to 5185 pale yellow to light green eggs about 1.2 mm in diameter are produced by each female. The eggs hatch in 9 days at 68°F.

Importance

Ammocoetes have been sold as bait for sport fish in Québec but this is no longer permitted.

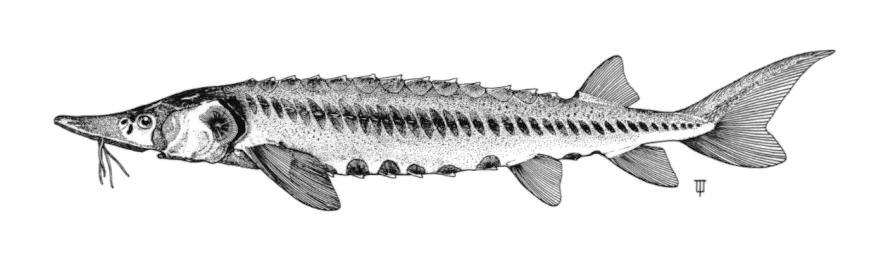

Acipenseridae - Sturgeons - Esturgeons

Sturgeons are found in fresh and coastal waters around the Northern Hemisphere. There are 24 species with 5 occurring in Canada and 1 in the NCR. This family contains the largest freshwater fishes and life span is reported to exceed 150 years although fish of great size are difficult to age accurately. Some species live entirely in fresh water while others are anadromous, spending some time in the sea but returning to fresh water to spawn. The NCR species spends all its life in fresh water. Sturgeon roe or eggs are known as caviar and form an expensive delicacy. The flesh is also eaten, and is tasty when smoked. The swimbladders of sturgeons have been converted to isinglass, a transparent gelatin used in a variety of products including as a wine and beer clarifier and in jams and jellies. The total Canadian catch of sturgeons in 1988 was 53 tonnes. Their migratory habits have made them victims of pollution and hydroelectric schemes and sturgeons are no longer as large nor as numerous as in the past. Slow growth makes them susceptible to overfishing. Fossils extend back 100 million years and related but extinct families to 310 million years ago.

Lake Sturgeon / Esturgeon jaune

Acipenser fulvescens Rafinesque, 1817

Taxonomy

Other common name include Freshwater, Common, Great Lakes, Red, Ruddy, Black, Rock, Stone, Dogface, Shellback or Bony Sturgeon, Smoothback, Rubber Nose, Esturgeon de lac and Camus; or for young - Escargot, Maillé and Charbonnier. Acipenser is from the Latin for "sturgeon" and fulvescens means "brownish".

Key CharactersThis species is unique in having 5 rows of bony scutes or plates along the body, (1 dorsal, 2 lateral and 2 ventrolateral), 4 barbels in front of the transverse mouth under an elongate snout, no teeth in adults, and an upturned caudal fin skeleton (heterocercal) such that the upper tail lobe is larger than the lower.

Description

Dorsal fin rays 35-40, anal fin rays 25-30, dorsal plates 8-17, lateral plates 29-43, ventral plates 6-12, 1 large plate between the caudal fin and the anal fin in addition to the fulcrum (a flat bony plate), and 25-40 gill rakers. The scutes may almost disappear in old sturgeons but are sharp and obvious in young. The skeleton is cartilaginous, there is a spiracle and a spiral intestinal valve.

Colour

Back and upper flank dark brown, olive-green or grey and belly white to yellow-white. Flanks may be reddish. Fins are dark brown or grey. Body cavity organs are black but the peritoneum is silvery and only slightly pigmented. Specimens smaller than 30 cm have 2 black blotches on the upper snout, a black blotch between the dorsal and lateral plates above the pectoral fin base and another similarly positioned below the dorsal fin, and smaller spots on much of the rest of the head and body. Lower parts of the body are greenish.

Size

Reaches an estimated 312.0 cm and 184.57 kg, the largest freshwater fish in North America. The world, all-tackle angling record wa recognised as a 41.84 kg fish caught in the Kettle River, Minnesota in 1986 although much larger fish have been caught on rod and line. The Ontario record as of the year 2000 from Georgian Bay weighed 76.2 kg and is the International Game Fish Association Record (1999). The fish was caught in 1982. Newspaper records of large sturgeons caught in the Ottawa River are reprinted in Szabo (2004) and listed here. One fish snagged in Lac Deschênes had a sleigh harness entangled around its gills, apparently lost ten years before when a horse fell through the ice (Pembroke Observer, 7 June 1901, p. 1). Catches in the Ottawa River include a 5' 3", 85 lb one caught between Aylmer and Ottawa (Toronto Star, 22 May 1908, p. 1), a 5'4", 100 lb one caught illegally - the fisherman was fined (Globe and Mail, 2 November 1921), a 5'6" (1.65 m), 175 lb (79.5 kg) one from Lac Deschênes that had to be towed 2 miles to shore to be landed (Globe and Mail, 17 May 1927, p. 1; Harkness and Dymond (1961); McAllister and Coad (1975)), a 217 lb (98.5 kg) one from near Montebello that either bit or swiped the angler on landing (Globe and Mail, 26 March 1931, p 1; Toronto Star, 26 March 1931, p. 6; Butler, 2006; Harkness and Dymond (1961); Egan (2000)), a 5', 75 lb one caught with a minnow net (Toronto Star, 3 July 1939, p. 26), a 4' one caught by its tail from a ferry between Rockliffe and Gatineau Point (Toronto Star, 8 June 1949, p. 48), a 60 lb one that leaped out of the water at Rockliffe boathouse (Toronto Star, 19 August 1949, p. 1), a 3', 15 lb one that jumped into a boat - it apparently was trying to rub leeches of its body on the side of the boat (Toronto Star, 2 July 1953, p. 10), a 51.5", 45 lb one near Orleans (Globe and Mail, 23 June 1962, p. 4), and a 5'10" (1.8 m), 107 lb (48.6 kg) one from the Deschênes Rapids (Ottawa Citizen, 7 July 1972, p. 3; Cote (1972); Leggett (1975)).

Found from western Québec including James Bay, all of Ontario and most of Manitoba and westward in the North Saskatchewan River to Alberta. South to Alabama, northern Mississippi and Arkansas west of the Appalachian Mountains. In the NCR it is restricted to the Ottawa River and mouths of tributaries, with more captures below Ottawa than above in the NCR (see also Haxton(2008) for additional map points). .

Origin

This species colonised the NCR from a Mississippian refugium (Guénette et al., 1993; Ferguson and Duckworth, 1997).

Habitat

Lake Sturgeon are found in shallow areas of lakes and large rivers at about 4-9 m although they may descend to 43 m. These shallow areas are the highly productive shoals where food items are most available. Mostly the bottom is mud. Older fish tend to be in deeper waters and all age groups move away from shallower waters in summer to return in fall, presumably in response to temperature and oxygen changes. They are not usually found in water over 23.8°C and prefer waters at 15-17°C. Occasionally sturgeon are reported to jump and can end up in boats (Harkness and Dymond, 1961; Egan, 2000; 2003). A 50 lb (22.7 kg) sturgeon 58 inches (1.47 m) long leaped out of the water and landed in a rowboat crewed by two girls on the Ottawa River. Sturgeon are quiet tough and can survive several hours out of water and are relatively easy to tag, spine clip and weigh and measure in mark-recapture studies when water and air temperatures are cool.

Kerr et al. (2010) review Lake Sturgeon habitat requirements and the effects of habitat changes such as dams. A barrier-free distance of 250-300 km of lake/river range is required for a self-sustaining population, for example. Wozney et al. (2011) found that habitat fragmentation by dams had not caused any negative genetic impacts in the Ottawa River, presumably because of the long generation time of this species. However, habitats would have to be reconnected for the long-term conservation of the sturgeon.

Age and Growth

Accurate age determination is difficult in long-lived species like sturgeons. Maximum female age is estimated to be 96 years and for males 55 years. There is a report of one fish aged at 154 years from Lake of the Woods. Growth is slower in the north than the south and fish are older. Maturity has been estimated at 8-20 years for males and 14-33 for females, varying with locality. St. Lawrence River female sturgeon reach sexual maturity at an estimated 27 years and 1.33 m and the mean interval between spawnings is 9.4-9.7 years, higher than reports for other populations.

Ottawa River fish mature at 19-20 years and 30 inches (76.2 cm) for males and 26 years and 33 inches (83.8 cm) for females with few males exceeding 45-50 years and females living longer (Harkness and Dymond, 1961). In the Hull-Carillon section of the Ottawa River, 94% of the sturgeon caught in a 1988 study were less than 27 years old (the mean age of first maturity of females) and the species here is not very abundant nor as old, long or heavy as compared to those in the St. Lawrence River (Fournier, 1988; Fortin et al., 1992). Haxton (2002) sampled sturgeons in the Ottawa River over a 5-year period (1997-2001). Three of his areas fall within the NCR - Lac des Chats (above the Chats Falls Dam, mostly upriver of the NCR, sampled 1998), Lac Deschênes (Chats Falls Dam to Chaudière Falls, wholly within the NCR, sampled in 2000) and Lac Dollard des Ormeaux (below the Chaudière Falls to the Carillon Dam, much of it within the NCR, sampled in 2001). Eleven sturgeon were taken in Lac des Chats, none in Lac Deschênes, and 42 in Lac Dollard des Ormeaux. Sturgeon were more abundant in some sections higher up the Ottawa River outside the NCR. The mean total length for Lac des Chats sturgeon was 109.9 cm and mean weight was 8450 g. The mean total length for Lac Dollard des Ormeaux sturgeon was 78.7 cm and mean weight was 2039 g. The latter population showed some signs of recruitment despite being downriver of the NCR. The sex ratio is about 1:1 at birth but by age 40 years it is 6:1 in favour of females. Garvey (2001) found only 8 sturgeon in the disturbed Lac Deschenes over 298.21 hours of fishing compared to 117 fish over 152 hours in the undisturbed Lower Allumette, upriver. Mean total length for Lac Deschenes fish was 121 cm and mean weight was 10.39 kg.

A comparison of the spawning population below the Chats Generating Station was made for sample years 2001-2004 and the study of Dubreuil and Cuerrier (1950) for 1949 fish by Haxton (2006). The spawning stock in 2003 was estimated to be 202 fish, mean size was greater (118.0 cm total length for 2001-2004 compared to 101.7 cm in 1949), weight-length relationships did not vary between studies, and fish less than 110 cm total length comprised only 31.1% of the sample compared to a majority of 69.9% in 1949. This latter observation suggest the population is suffering a recruitment problem. Recruitment did occur because fish were aged at 13 to 46 years, and therefore were not relicts of the pre-1949 population. Ages in the 1949 survey were 15-62 years. Interestingly only males were found in spawning condition, suggesting spawning females could be rare in this section (Lac Deschênes) of the Ottawa River enclosed by dams at Chats and Ottawa.

Haxton (2008) summarises knowledge of sturgeon in the Ottawa River and found the greatest abundance in unimpounded river reaches, a condition found outside the NCR. The von Bertalanffy growth equation for Ottawa River fish was Lt = 133.7(1-exp-0.058(t-(-3))) and condition was described by w = 5.6 x 10-4l3.50. Length and age at 50% maturity was 106.7 cm and 20.4 years fro males and 112.2 cm and 25.4 years for females Fecundity was estimated at 12,170 eggs/kg. Annual mortality was estimated at 15%.

Food

Food is slurped from bottom sediments and includes a wide variety of animal and plant material found in and on the bottom. Sediment is also taken in and ejected from the gill slits or the mouth. The food is detected by the barbels which lightly touch the bottom as the sturgeon swims slowly along. The tubular mouth is protruded as soon as food is detected. Recorded food items are crayfish, other crustaceans, clams, snails, aquatic insects, fish eggs (such as those of Yellow Perch), algae and rarely fish. It is not considered to be a serious predator on the eggs of other fishes. Sturgeon may leap out of the water, a habit attributed to efforts to rid themselves of parasitic lampreys. 61 Silver Lampreys have been recorded on a single Lake Sturgeon, 1.3 m long and 16 kg in weight, caught in the St. Lawrence River, although these were not considered to be enough to kill the sturgeon.

Reproduction

Spawning occurs in April to June at 9-18°C in flowing water or rocky lake margins with wave action. In the Ottawa River at the Fitzroy-Quyon Rapids in 1949 the period was 29 May to 6 June at 56-60°F (10.0-15.6°C) (Harkness and Dymond, 1961). Sturgeon also spawn downstream from Chaudière Falls below Victoria Island in the heart of Ottawa (Haxton and Chubbock, 2002). Peak spawning in Lac des Chats was 12 June in 2006 and 5-15 June in 2007, and in Lac Deschênes was 4-8 June 2001, 4-12 June in 2003 and 8-14 June in 2004. Depths are usually 0.6-4.7 m for spawning generally. Lake populations may migrate up rivers for 400 km to reach spawning grounds although the distance traveled is usually less and fish are generally sedentary outside spawning. Males arrive first on the spawning grounds. The large female is in spawning condition for a short time and is flanked by up to 6 males. The spawning process may involve splashing, vibrations and leaps clear of the water. Eggs and sperm are shed at intervals over a few days and the eggs adhere to rocks. The spawning act lasts only 5 seconds. The eggs are black, up to 3.5 mm in diameter and in very large fish could exceed 3 million. Ottawa River fish produced up to 7179 eggs per pound of fish (Harkness and Dymond, 1961) or 54,000 eggs per kilogramme of ovary (Dubreuil and Cuerrier, 1950). Incubation lasts 5-8 days at 15.6-17.8°C. Spawning occurs at estimated intervals of 1-7 years in males and 4-9 years in females, with longer intervals in the north.

Importance

This species has been used historically for food fresh or smoked, the eggs as caviar, the swimbladder as isinglass (a form of gelatin) and skin as leather. Oil from sturgeon in the Ottawa River has been used by native peoples, mixed with ochre, to delimit pictographs at Oiseau Rock in western Pontiac County, Québec (www.cycloparcppj.org/oiseau/rocheroiseau_a.htm, downloaded 18 April 2005). Haxton (2002) reviews literature that show this species was abundant in the Ottawa River before 1900 and was harvested for food by aboriginal people (see also Gaffield (1997)). Dymond (1939) records catches from 1881 onward in the general vicinity of the NCR but trends cannot be determined as fisheries data is recorded from different areas at different dates. For example, in 1898 the catch was 63,450 lbs (28,806 kg) in the Ottawa River from Carillon to Pontiac in Québec, the highest recorded. Harkness and Dymond (1961) report past commercial fisheries in the Ottawa River and its lake-like expansions, and the Madawaska River and the Mississippi River and Lake (now absent from the latter two river basins). Commercial fisheries for sturgeons above and below Hull from the Québec side of the Ottawa River is documented by Pluritec (1982b). Fournier (1988) estimated that the fishery in the Hull-Carillon section of the Ottawa River yielded 0.7 kg/ha; Fortin et al. (1992) reporting a catch of about 10 tonnes by three fishermen in this sector. 94% of the catch was less than 27 years old, the age at which more than half the fish are mature. The section of river above Hull contained older fish and exploitation was less strong. The population was overexploited. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) and Gouvernement du Québec Faune et Parcs (1999) report that a strictly controlled tag and quota system was to be implemented on the Ottawa River to ensure a sustainable harvest rate of 0.1 kg/ha/yr. Ontario fishermen are prohibited from harvesting sturgeon. Séguin (1970) mentions a request to open a commercial fishery on the Gatineau River but this apparently never developed.

Egan (2000) records a commercial harvest of this sturgeon on the Ottawa River as early as 1883 although this is from areas upriver of the NCR near Renfrew and Rolphton. The sturgeon were caught on longlines left overnight. the flesh was smoked, an oil and isinglass extracted, and caviar taken. Gutted sturgeon were sent in dry ice to New York City in the early 1950s and the roe was sent to a packer in North Bay. Today, although commercial fishing for this species is not allowed in the NCR the value of caviar elsewhere is $200/kg and flesh is $40/kg, and by 2006 $400/kg (Butler, 2006). The caviar is reputedly second only to that of Caspian Sea sturgeons.

Dams, pollution and overfishing have reduced populations in Canada. Populations in the Ottawa River were reduced by dam construction which blocks spawning, nursery and feeding migrations, fragments populations and alters habitats, by land clearance for agriculture and logging, by pollution from saw mills and untreated sewage, and by intensive commercial fishing at least in the past (Guénette et al., 1993; Ferguson and Duckworth, 1997; Haxton, 2002; Haxton and Findlay, 2008). Even blasting for a marina on the Ottawa River killed sturgeons around 1970. The Lac Dollards des Ormeaux stretch of the Ottawa River was closed to fishing for sturgeon in 1990 because of a decline in abundance and high contaminant levels (Haxton and Chubbock, 2002). On 1 July 2008 Ontario instituted a zero catch and possession limit on recreational fishing for sturgeon, except for traditional usage.

88,287 kg were caught in 1961 in Canadian waters but the Lake Erie catch alone in the late nineteenth century exceeded 2,268,000 kg. In the Québec portion of the St. Lawrence River commercial yields are very high, up to 3.4 kg/ha with 138.8 tonnes being taken in 1986. These stocks have been over-exploited. They are caught with gill nets, longlines with up to 600 hooks, and seines. One unexpected detrimental factor to sturgeon survival is discarded rubber bands used by Canada Post to bind mail. These are washed through storm sewers into the St. Lawrence River where they become threaded onto the pointed snouts of sturgeon grubbing in the mud for food. Out of 800 fish studied near Québec, 64 had elastic bands. The bands become embedded in the sturgeon's head, interfere with feeding and leave the fish open to infection. Sturgeon with bands weigh one-third less than normal.

It is not a major sport fish in Canada but large specimens are occasionally hooked or snagged to the great surprise of the angler. Some anglers do pursue this giant fish using minnows, meat or worms as bait or spinning gear and hand lines. Sturgeon fight strongly and may leap. There are catches of one sturgeon for every 4 hours fishing effort near Medicine Hat, Alberta. There are winter spear fisheries in the U.S.A. and they are caught through the ice at Petrie Island on the Ottawa River (local informant, 10 February 2007). The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources publishes a print and on-line "Guide to Eating Ontario Sport Fish" (www.mnr.gov.on.ca/MNR/) and has advisory limits for eating this species in the Ottawa River. Environnement Québec also has recommended limits, in meals per month (1 to 8) for size of fish (small, medium or large), for such areas as Lac Deschênes at Aylmer and Quyon, Deschênes Rapids, the Ottawa River below Gatineau, above Hull, and at Masson, the Lièvre River above and below Buckingham and the Gatineau River at Chelsea, among others (www.menv.gouv.qc.ca, downloaded 13 October 2004). As these limits are apt to change, anglers consuming this fish should consult the most recent version.

This species was placed in the "Not at Risk" category in 1986 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (Houston, 1987) but is listed as threatened in Canada by Peterson et al. (2003).

Lepisosteidae - Gars - Lépisostés

Gars are found in freshwaters of North and Central Americac and Cuba, sometimes entering brackish water and rarely the sea. There are 7 species with 2 in Canada and 1 in the NCR.

Gars have elongate jaws ("gar" is Old English for spear) filled with needle-like teeth. The ganoid scales are heavy, peg and groove hinged, non-overlapping, rhombic and plate-like, forming an effective armour. The tail is abbreviate heterocercal, externally appearing symmetrical but heterocercal internally. An upper tail lobe disappears with growth. There are 3 branchiostegal rays. The swimbladder has a rich blood supply enabling the fish to breathe air through a connection to the gut. A school of gars will break the water surface to breathe air at the same time and reduce the chances of attack by predators. Vertebrae are peculiar in having an opisthocoelous shape - anterior end convex, posterior end concave, a kind of ball and socket joint - which is almost unique in fishes and more usually associated with amphibians and reptiles. Dorsal and anal fins are near the tail. They lack spines but have fulcra (angled scales) on their anterior edge. The alligator gar of the southern U.S.A. and central America is the largest species at 3 m and over 158 kg.

Cretaceous and Eocene fossil gars are known from North America, Europe, India and West Africa. Fossil gars have been reported from Ellesmere Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, well north of their modern distribution. An Upper Cretaceous coprolite (fossil faecal matter) from Alberta contained remains of gar scales and vertebrae. The gar was probably eaten by a crocodile, an indication of the different faunas that Lepisosteus species have lived with in Canada.

Gars favour shallow, weedy areas of lakes and rivers. They are ambush predators, lying still or quietly stalking prey until it can be seized by a sudden rush. Their food is almost entirely fishes. They make excellent subjects for home aquaria when young and for public aquaria when large. Gars are not sought after by anglers since they are hard to hook in their elongate, bony jaws, but a few enthusiasts specialize in their capture. They are not a commercial fishery item. Gar scales and skins are occasionally made into jewelery, picture frames, purses and boxes. The scales can be highly polished.

Longnose Gar / Lépisosté osseux

Lepisosteus osseus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Taxonomy

Other common names include Garpike, Northern Longnose Gar, Billy Gar, Billfish, Needlenose, Northern Mailed Fish, Pin-nose Gar, Bonypike, Scissorbill and Poisson armé.

Key Characters

This species is the only gar in the NCR and is readily identified by the very elongate snout armed with needle-like teeth.

Description

This species is distinguished by the long, narrow snout 14-18 times longer than minimum width, 57-66 lateral line scales and spots only on the body from the pelvic fins to the caudal peduncle and on the dorsal, anal and caudal fins. Gill rakers 14-31. Dorsal fin rays 6-9, anal rays 7-10, pectoral rays 10-13 and 6 pelvic rays. Young fish have dorsal and ventral filaments on the caudal fin. The swimming young fish appears to be moved by a propeller as these filaments vibrate rapidly.

Colour

Adults are grey or olive-brown to dark green fading to pale green or silver on the flanks and white on the belly. Colour is variable with habitat. Flank scales often outlined in black. The dorsal, anal and caudal fins are pale brown to yellow and spotted. Pectoral and pelvic fins are dusky without spots. Young have a narrow reddish-brown or black stripe on the back, and one on the mid-flank which has a wavy upper edge. Above the flank band they are brown to black, below brown with white or cream areas.

Size

Reaches over 2 m and 37.2 kg. The world, all-tackle angling record weighed 22.82 kg and came from the Trinity River, Texas in 1954, but this may have been another species, probably an Alligator Gar. A gar weighing 16 lbs (7.3 kg) and measuring 40 inches (1.02 m) in length was caught near Rideau Falls in the Ottawa River (Anonymous, 1974b), a 13.9 lbs (6.3 kg) gar from the Ottawa River on 3 July 1973 ( www.canadian-sportfishing.com/NationalFishRegistry/Catch_And_Keep1.asp), a 15.2 lbs (6.9 kg) fish was caught by Scott Thibeault in the Ottawa River on 1 June 2001 (www.ofah.org/Registry/fish.cfm?RecID=23, downloaded 14 May 2004), a 51 inch fish with a 16 inch girth was caught by Jeff Cyr in the Ottawa River on 6 October 1994 ( www.canadian-sportfishing.com/NationalFishRegistry/Live_Release1.asp, downloaded 13 June 2003), and gar about 20 lbs and 54-57 inches long are reported form the Ottawa River (G. Barnardo, in email, 10 June 2004).

In Canada found from the St. Lawrence River basin, the Great Lakes, but rare in Lake Superior, across southern Ontario. In the U.S.A. found in the Mississippi River, Great Lakes and southern Atlantic coastal basins, absent from the eastern American mountains. In the NCR it is found in the Ottawa River and mouths of tributary rivers.

Origin

This species entered the NCR from a Mississippian or possibly an Atlantic coastal refugium (Mandrak and Crossman, 1992).

Habitat

It is usually found in quiet, weedy shallows of lakes and larger rivers and, because of its air-breathing ability, enters hot stagnant waters to feed where other predators could not survive. The preferred temperature is said to be 33.1°C. Gars can be seen in summer hovering motionless at the surface although they dive rapidly out of sight if disturbed. They can also be seen at night in summer when canoeing in Shirley's Bay, the most common mid- to large-sized fish in the bay (Eric Snyder, pers comm., 7 January 2008).

Age and Growth

Maximum age is 27 years for males and 32 years for females. Females grow faster and the sex ratio of males to females changes from about 262 to 100 in early life to only 8 males per 100 females after age 10.The growth of young is the fastest of any North American freshwater fish. These gar are mature at 6 years and 50.0 cm.

Food

Food is usually all fishes of suitable size, more rarely frogs, crayfish and even small aquatic mammals. Prey is seized by a sideways slash of the snout after a dart or drift from cover. The prey, impaled on the teeth, is manoeuvred so that is can be swallowed head first.

Reproduction

Spawning occurs in spring and summer at 20°C or warmer usually in weedy shallows. Ripe gar that were presumed to be spawning were caught in the lower Carp River, Fitzroy Harbour Provincial Park on 10 June 1964 (McAllister and Coad, 1975). Water temperature was 23°C and the current medium over a rocky bottom. They were still spawning here in 2009, on the afternoon of June 6th (the night of a full moon), and in fewer numbers on the following morning. Stewart Fast (pers. comm., 19 June 2009) observed spawning of up to 200 gar swimming on top of each other, at times 4 or 5 deep, in 75 cm deep pools downstream of a small waterfall. Orange to brown eggs were seen on rocks and plants. Campers were able to pick up fish by hand. Some fish were an estimated 125 cm long. Gar are also reported as spawning in a large pool in the Ottawa River at the end of Woodroffe Avenue in June (www.ottawariverkeeper.ca/riverkeeper/ecology/@200_river/phen.html) and on 13 June 2008 in the Quyon River at the lower bridge (see below). The female is approached by up to 15 males which she leads in an elliptical path. The males nudge the female's belly area with their snouts while oriented head down. Males and female quiver and eggs and sperm are released. The eggs are scattered and attach to vegetation. The eggs are dark green, perhaps as camouflage, and measure 3.2 mm in diameter. The number of eggs may be as high as 77,156. Eggs are poisonous to birds, mammals and humans, and can kill smaller mammals. In Ontario gar eggs have been found in the nests of Smallmouth Bass and such nests had a higher success rate than nests with only bass eggs. Whether gar are deliberately spawning over bass nests is uncertain, they may merely be in the same area. However they do gain an advantage because the bass defends the nest against predators. Curiously, gar eggs are eaten by other fish despite being reputedly poisonous to mammals. The bass may benefit by having larger gar eggs and larvae in the nest to distract predators from the smaller bass eggs and larvae. Also more eggs and larvae of whatever species lessens the chance of individual loss to a single predatory attempt. Conversely, the male bass has more eggs to guard and the larger gar eggs are more attractive to predators, but on balance both fish species benefit. The young gar have an adhesive pad on the snout tip which attaches them to weeds. After about 9 weeks the yolk-sac is absorbed, the gar no longer hangs vertically from vegetation and is free-swimming. They grow very rapidly, as much as 3.9 mm a day, much faster than most other Canadian freshwater fishes.

Importance

Gar are considered a pest because they eat other fishes and are often killed by fish. They have been pursued in the NCR by anglers who specialise in trying to catch this species with its narrow bony mouth. They are edible, better tasting when smoked, although they are hard to clean because of the bony armour. The flesh must be carefully cleaned of the eggs before eating as these are thought to be poisonous although there is some dispute about this.

Amiidae - Bowfins - Poissons-castors

The Bowfin is found in freshwaters of eastern North America and is the only member of its family. Fossil amiids are known world-wide and the oldest are of Jurassic age, 135-195 million years ago. Eocene amiids have been described from British Columbia, Palaeocene and Cretaceous ones from Alberta and Palaeocene and Oligocene ones from Saskatchewan. The genus Amia has been extant for 70 million years; evolutionary change is very slow.

The general body form of a Bowfin is unmistakable. In addition there is a large bony structure on the underside of the head between the lower jaws known as a gular plate. Branchiostegal rays number 10-13. There are no pyloric caeca. The caudal fin is an abbreviate heterocercal one. Heterocercal tails have the vertebral column turned upwards into the upper lobe of the fin, which is longer than the lower lobe. In the Bowfin, the lobes are not noticeably different in size. Scales are cycloid but are reinforced with ganoin. Some teeth are pointed canines while others are peg-like. Gill rakers are reduced to knobs but bear small spines.

The Bowfin's relationships to other fishes have long been discussed and large monographs have been written on the details of its anatomy. It is, in a sense, a living fossil, since many related families and species were widespread in the Jurassic and Cretaceous periods, but the Bowfin is the only surviving representative. Unlike sturgeons, the skeleton is bony but it has the heterocercal tail and a trace of a spiral valve. The gular plate, heavy bone plates on the head, and ganoin containing scales are also ancient characters. It is now considered to be related to the Teleostei and, with its fossil relatives, is equal in rank to the thousands of teleost species. The Bowfin swimbladder can be used as a lung since it has an opening to the gut and the internal surface is well-supplied with blood vessels. This fish can survive out of water for a day, and thrives in low oxygen waters such as stagnant swamps. Recent studies have shown that Bowfins cannot aestivate like the tropical lungfishes because they cannot detoxify ammonia waste or reduce metabolism and they die after 3-5 days of air exposure.

Bowfin / Poisson-castor

Amia calva Linnaeus, 1766

Taxonomy

Other common names include Dogfish, Mudfish, Mud Pike, Grindle, Grinnell, Griddle, Spot-tail, Lawyer, Cottonfish, Blackfish, Speckled Cat, Scaled Ling, Beaverfish, Cypress Trout, Amie, Poisson de marais and Choupique. Bowfin refers to the long, undulating dorsal fin.

Key Characters

The gular plate, a large bony structure between the lower jaws on the underside of the head, identifies this freshwater fish.

Description

The dorsal fin has 42-58 soft rays, the anal fin 9-12 rays and the pectoral fin 16-18 rays. There are 62-70 scales in a complete lateral line. The anterior nostrils have barbel-like flap.

Colour

The back is a dark-olive or brownish with the flanks mottled, marbled or reticulated with olive and yellow. The belly varies from white to light green. The dorsal fin is dark olive with 2 dark broken stripes, the anal, pelvic and pectoral fins are bright green. Males have an eye spot at the upper caudal fin base. The spot is dark and about twice as large as the eye and is surrounded by an orange or yellow halo. This spot is absent in females. Such eyespots are used to deflect the attack of predators from the eye to the less important tail, which may well give the predator a slap in the face! The anal, pectoral and pelvic fins have orange bases and tips in males. Young fish are lighter overall and have a black margin to the dorsal and caudal fins. There is a narrow stripe from the snout through the eye onto the opercle. Young smaller than 3-4 cm are black.

Size

Attains 109 cm and 9.87 kg. The world, all-tackle record from Florence, South Carolina in 1980 weighed 9.75 kg and a 6.7 kg fish was taken from Whitefish Lake, Ontario.

Found from the St. Lawrence and Lake Champlain drainage of southern Québec westward around the Great Lakes in southern Ontario as far as Minnesota. In the south it reaches Florida and Texas. There are no specimens in a museum collection definitively from the NCR. Halkett (1906) mentioned two specimens from the Ottawa River in the Fisheries Museum, Ottawa and Prince et al. (1906) also reported two specimens in the Museum from the Ottawa River (presumably the same two fish) but did note they may not have been caught near "the district". Bergeron and Brousseau (1982) and Bernatchez and Giroux (2000) map this species within the NCR but may have based this on Prince et al. (1906). However competent fishermen familiar with a wide variety of fishes have reported it from Britannia in the late 1940s, Rockland; and even below the Parliament Buildings, all in the Ottawa River (J. McLoughlin, personal communication, 1986; D. Brunton, in letter, 1987; E. Hendrycks, personal communication, 2000). Chabot and Caron (1996) map a specimen from the Ottawa River, near the mouth of the Gatineau River.

Origin

This species entered the NCR from a Mississippian refugium (Mandrak and Crossman, 1992).

Habitat

Bowfins prefer warm quieter waters with a lot of vegetation in lakes and river backwaters. They can survive temperatures up to 35°C in stagnant waters which other predatory fish cannot utilise. However they can be found too in clear water bodies that are quite cool. Bowfins gulp air at the surface even in well-oxygenated water. Their preferred temperature is 30.5°C. Bowfins can aestivate for short periods in a moist chamber, 20 cm in diameter and 10 cm below the soil surface when flood waters recede.

Age and Growth

Life span may exceed 30 years. Males are smaller than females and probably do not live as long. Bowfins become sexually mature at 3-5 years of age when they are about 61 cm (females) and 45.7 cm (males). Growth is rapid with some fish exceeding 20 cm in the first year of life.

Food

Food is mainly other fishes, with some crayfishes, aquatic insects and frogs, taken at night after moving into shallower water. The Bowfin feeds by a rapid lunge, opening the mouth to suck in the prey. The opening and closing of the mouth takes about 0.075 seconds. They can also move very stealthily by undulating the dorsal fin, moving both backwards and forwards.

Reproduction

This species spawns from April to June depending on latitude. Nests are constructed by the male in shallow (usually less than 1.5 m), weedy areas of lakes and rivers. The nests are under logs or other objects, or are circular areas up to 76 cm across where all vegetation has been bitten off and removed. The male defends his nest against other males and during the spawning season torn fins are not unusual as nests may be quite close together. Spawning takes place at 16-19°C when the male entices a female into the nest, circles her for 10-15 minutes while she lies on the bottom of the nest, and nips her snout and flanks. The male then lies with the female, their fins vibrate rapidly and eggs and sperm are released within a minute. This may happen 4-5 times over 1-2 hours. Several females may spawn with one male and each female may deposit eggs in more than one nest. Eggs number up to 64,000 in females but number up to 5000 in nests. They stick to the plant roots or gravel in the bottom of the nest. The male guards the eggs and fans them with his pectoral fins. Eggs are 2.8 x 2.2 mm in dimensions. The eggs hatch in 8-10 days and the young use an adhesive snout organ to attach to vegetation for a further 7-9 days while the yolk-sac is absorbed. The male continues to guard and herd the young fry until they are about 10 cm long. The fry form into a ball which follows the male. So defensive are males, that one attempted to attack a human standing on the bank, coming 20 cm or so out of the water and repeating the attack several times.

Importance

The Bowfin is a good sport fish on light tackle, but is seldom fished for and is very rare in the NCR. Some are taken elsewhere by spearing while diving. It is edible, though not particularly tasty, and some commercial catches in Ontario have been sent to the United States where it is a more familiar food fish and better appreciated. "Cajun caviar" is made out of the roe in Louisiana. Small Bowfins are excellent aquarium fish because of their "lung", colouration and predatory habits.

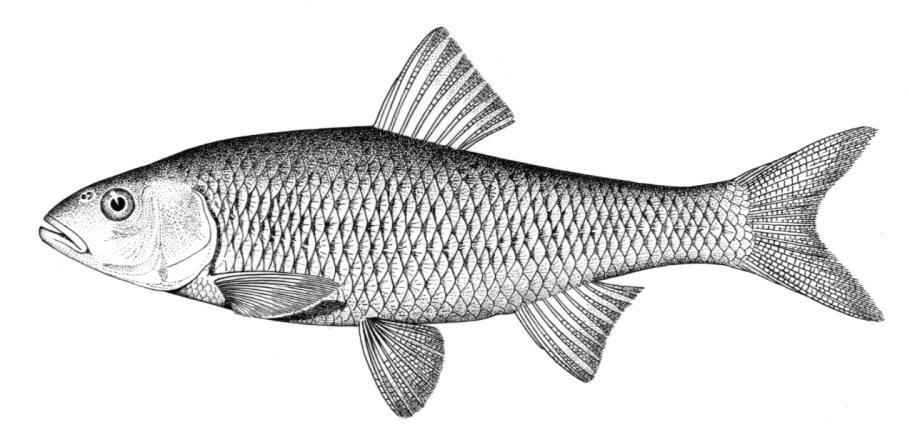

Hiodontidae - Mooneyes - Laquaiches

The Mooneyes are found only in North American fresh waters in central Atlantic, Arctic and Gulf of Mexico drainages. There are only 2 species, both found in Canada, with 1 in the NCR.

These moderate-sized fishes are similar in appearance to Herrings but have teeth on the tongue, roof of the mouth and jaws, and a dorsal fin far back over the elongate anal fin. There are 7 pelvic fin rays, a pelvic axillary process, 7-10 branchiostegal rays, a subopercular bone is present on the side of the head and scales in the lateral line number 51-62. There is a ventral keel to the body but no scutes as in herrings. Scales are cycloid. The swimbladder is connected to the skull. The eyes are large and far forward on the head near the rounded snout. There are adipose eyelids. There is a single pyloric caecum.

A unique feature is that eggs are ovulated directly into the body cavity and not carried externally via oviducts as in most bony fishes.

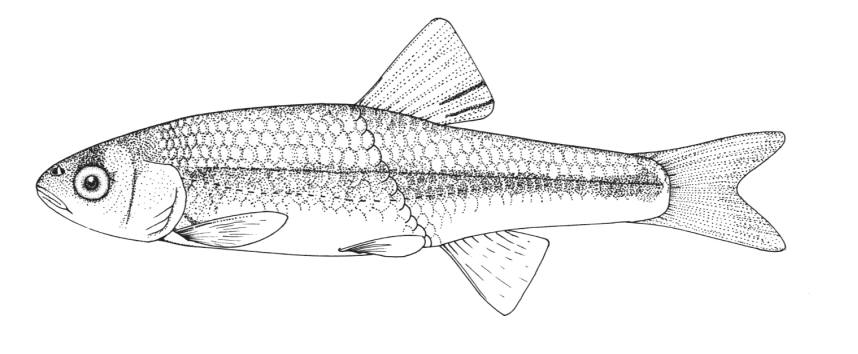

Mooneye / Laquaiche argentée

Hiodon tergisus Le Sueur, 1818

Taxonomy

Other common names include Toothed Herring, River Whitefish, Freshwater Herring, Cisco and White Shad. Locally called whitefish (Hopkins, 2000).

Key Characters

This species is the only member of its family in the NCR and is characterised by having a fleshy ventral keel from the pelvic to the anal fins, a dorsal fin origin in front of the anal fin origin, a long anal fin, a pelvic axillary process, no adipose fin, teeth in the jaws, and the mouth extending at most to mid-pupil level.

Description

Dorsal fin rays 10-14, anal rays 26-33 and pectoral rays 13-15. Scales in lateral line 51-60. Gill rakers 11-17. The eye is large. The anal fin base has 2-3 rows of small scales and, in males, the anterior part of the anal fin is greatly enlarged leaving the margin behind strongly concave. Males also show a concavity on the body over the anterior anal fin base rather like a depression caused by a pressed thumb.Colour

Colour is olive to brown on the back with a steel-blue sheen, flanks are silvery and the belly white. Fins are dusky, and a black stripe margins the leading edge of the pectoral fin. Spawning males and females have a pinkish hue on their fins and bellies. The eyes are golden above and silvery below.

Size

Reaches 47.0 cm and 1.1 kg. A Bay of Quinte, Ontario fish weighed 0.65 kg and is the Canadian fishing record.

Found from the James Bay lowlands of northeastern Ontario and adjacent Québec, south through the Ottawa River basin to the upper St. Lawrence and Lake Champlain, and lakes Ontario and Erie. Also in Lake of the Woods, southern Manitoba and Saskatchewan and the North and South Saskatchewan, Battle and Red Deer rivers of Alberta. In central U.S.A. south to the Gulf coast. In the NCR long known only from the Ottawa River but now recorded from the South Nation River at Casselman (29 May 2004).

Origin

This species entered the NCR from a Mississippian refugium.

Habitat

Mooneyes are found in both running and still shallow waters of lakes and rivers and appear to be sensitive to turbidity. They are usually taken at less than 11 m depth. Their preferred temperatures are 22-27°C. There is a migration up rivers to spawn in the spring.

Age and Growth

Males mature as early as 3 years while females are mature at 4-5 years, generally. Talajic (1980) studied this species in the Ottawa River above and below Ottawa. Life span is up to 13 years in the Ottawa River using scales for ageing verified by reading otoliths and vertebrae. Females live longer than males, the latter reaching 11 years in the Ottawa. Females mature at age 4 above and below Ottawa while males mature at 3 years (below Ottawa) and 4 years (above Ottawa). Females outnumber males by 2.2:1 (below Ottawa) and 3.4:1 (above Ottawa). Males and females showed no significant differences in length, weight and age although fish below Ottawa were significantly smaller than fish above Ottawa at an age. Growth is similar to other mooneye populations in Canada.

Food

Food includes insects, crustaceans such as crayfish and plankton, molluscs and small fishes. Ottawa River Mooneyes fed on ants, mayflies, dragonflies and beetles based on stomach contents (McAllister and Coad, 1975). Talajic (1980) found that the most important foods in the Ottawa River were Ephemeroptera, Trichoptera, Diptera and Coleoptera with smaller amounts of other aquatic insect larvae and, rarely, minnows, clams, spiders and crustaceans. Flying ants were also found in large numbers. Food depended on availability, varying through the year. Feeding often occurs at the surface in the evening and during the night when insects fallen on the water surface are taken aided by the light-sensitive eyes.

Reproduction

Spawning takes place in April-June and each female may produce up to 20,000 buoyant, blue-grey eggs of 2.1 mm diameter deposited over rocks and gravel in running water. Ripe females have been caught at the beginning of June near the mouth of the Gatineau River (McAllister and Coad, 1975) and Talajic (1974) found spawning from mid-May to mid-June at 10-14ºC. Talajic (1974) recorded up to an average of 9000 eggs of average diameter 2.24 mm, with the largest eggs to 2.98 mm. Comtois et al. (2006) report fish in reproductive stage V (spawning) in the lower Gatineau River from 10 Mayl to 23 June at 12.5-19ºC.

Importance

This species is of limited commercial importance, mostly on the U.S. side of Lake Erie. Various Herrings and Whitefishes have been listed erroneously as Mooneye in catch statistics. Commercial fisheries for mooneyes above and below Hull from the Québec side of the Ottawa River is documented by Pluritec (1982b), assuming "Laquaiche aux yeux d'or" is a mis-nomer for this species. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) and Gouvernement du Québec Faune et Parcs (1999) report one license is issued for this species in the Ottawa River (Carillon to Ottawa-Hull). It is caught by anglers who specialise in catching this unusual sport species using flies, worms, grasshoppers, minnows or lures on light tackle. It is best eaten spiced, smoked or fried with butter and onions as it is dry and tasteless when fresh

Anguillidae - Freshwater Eels - Anguilles d'eau douce

Freshwater eels are found world-wide in temperate to tropical waters except for the south Atlantic Ocean and the whole eastern Pacific Ocean. There are 16 species with 1 occurring in Canada and the NCR.

The term eel-like is based on the body shape of freshwater eels and includes the muscular slipperiness associated with this fish and its mucus-producing skin. Both dorsal and anal fins are long and join the tail fin. The dorsal fin begins well behind the pectoral fin level. There are no pelvic fins and the pectorals, when present, are on mid-flank. Scales are absent or when present small, embedded and cycloid. There is a lateral line. Jaws are strong and toothed. The gill openings are small and just in front of the pectoral fins. The anterior nostril is tubular

The life cycle of eels was unknown until Johannes Schmidt published his 1922 study based on years of collecting. Where the adults went on their seaward migration and where the elvers ascending rivers came from were a mystery. These eels are catadromous, living in freshwater but migrating to the sea to spawn and die. In the North Atlantic Ocean spawning occurs in the Sargasso Sea. The young eels or leptocephali (= thin head larvae) are distinctive being transparent and leaf-like. A newspaper can be read through the body of a leptocephalus. In this form they drift to the shores of America and Europe, transform into elvers with the more familiar eel-shape and move into rivers and lakes to feed and grow.

The biology of eels is based almost entirely on the freshwater phase of their life. Adults in freshwater develop large eyes, the gut degenerates and coloration changes in preparation for the migration to the Sargasso Sea. Adults were only caught in the deep ocean, at nearly 2000 m near the Bahamas, in 1977. The Sargasso spawning ground is deduced from collections of larvae across the Atlantic Ocean - the smallest and youngest larvae are found around the Sargasso Sea. The spawning grounds are at about 400 m, at a 17°C temperature and in saltier water than usual sea conditions according to some authors but since spawning adults have never been caught this remains dubious.

The theory advanced by D. W. Tucker in 1959 maintained that European Eels lack the energy resources in their migratory, spawning phase to reach the Sargasso Sea 7000 km from Europe. They are presumed to be following an instinct to head out to sea, dating from an earlier geological age when the Atlantic Ocean was narrower before the separation caused by Continental Drift. All European Eels die at sea and Europe is restocked by larvae drifting there spawned from American parents. The American populations are closer to the Sargasso and can make the journey easily. Differences between American and European eels are merely the consequence of different environmental regimes in different parts of the Sargasso. This theory has not found general acceptance but, if true, means that all European Eels can be harvested for food without depleting stocks. Eels are valued as food, particularly in Europe and Japan, but are not used as extensively in North America.

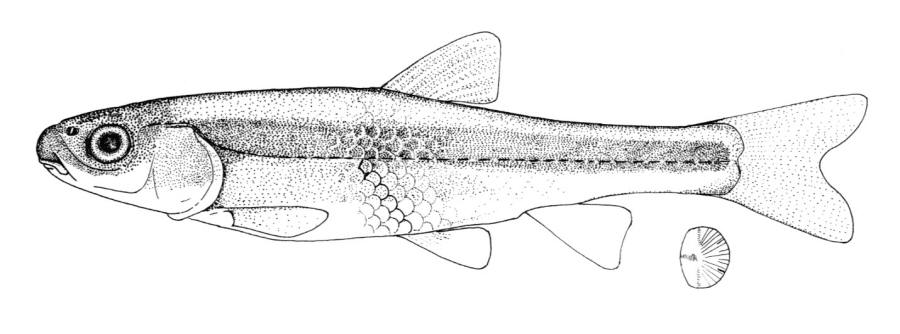

American Eel / Anguille d'Amérique

Anguilla rostrata (Lesueur, 1817)

Taxonomy

Other common names include Common Eel, Atlantic Eel, Boston Eel, Snakefish, Silver Eel, Yellow-bellied Eel, Bronze Eel, Black Eel or Green Eel and Anguille argentée.

Key Characters

The American Eel is distinguished by its shape, confluent dorsal, caudal and anal fins, the toothed jaws, and the single gill opening. Lampreys have a similar shape and confluent fins but have no jaws (teeth are in a sucking disc) and there are 7 gill openings.

Description